Pavel Violated the Constitution in the Style of Zeman and Masaryk: Do We Need a New System?

- Filip Turek

- Jan 18

- 7 min read

It is happening again. The President of the Republic has refused to appoint a minister. And once again, this act passes without major confrontation. This approach, however, only erodes the Constitution, and perhaps the time has already come for a radical step.

What exactly is the President of the Czech Republic allowed to do? In theory, this question should be clearly resolved by the Constitution of this country and by other laws within our legal system. In reality, however, the power of our head of state has never been based solely on these legal facts, but also on symbolism, personal authority, and the willingness of Czech governments to yield to them. This is not a new problem. On the contrary, it is as old as Czechoslovakia itself. Especially in modern times, it has become the center of growing uncertainty surrounding the Constitution itself—an uncertainty that both poles of our political scene are now willing to exploit. But if Czechs are willing to let their president refuse members of the government, has the time not come to introduce a new system of governance?

A (Semi-)Parliamentary Republic?

As the very title of this article suggests, problems between presidents and the parliamentary system already arose with the founder of the former Czechoslovakia. Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk was enchanted by the American presidential system during his foreign travels and wished precisely this type of republic for his new country. This makes sense: Masaryk and his Progressive Party were completely insignificant players in the parliamentary democracy of Austria and never achieved even a single percent of the vote in elections. Why, then, should his new country follow this old model when it could adopt the U.S. model, where presidents such as Lincoln and Roosevelt played a primary role?

Masaryk did not obtain his desired system, but the Constitution was modified according to his wishes and expanded to strengthen the position of the president. He subsequently played a primary role in the unstable political system of the First Republic, and Prague Castle became the birthplace of most parliamentary coalitions of that era. Edvard Beneš continued this practice, though he lacked the abilities and reputation of his predecessor, which led the situation from one problem to another. The authority of the president was clearly demonstrated during the Munich Crisis, when Beneš and the government of General Syrový appointed by him approved the cession of our territories to Germany without parliamentary approval.

There is little point in discussing the dictators of the communist era. However, even the restored democracy did not avoid disputes over parliamentary and presidential powers, which became a problem for all of its elected presidents. Václav Havel already engaged in an open dispute with then–Prime Minister Miloš Zeman over a ministerial appointment, during which Zeman stated, among other things: “As for some kind of personnel veto, I believe it would be in conflict with Article 68 of the Constitution.” This loyalty to the Constitution naturally lasted only as long as Zeman’s tenure as prime minister. President Václav Klaus also conducted several disputes over ministerial appointments, but both of the first presidents of the Czech Republic ultimately backed down from their objections.

The true champion in the struggle against the parliamentary republic arrived at Prague Castle only in 2013. Miloš Zeman likes to say that only a fool never changes his opinion, and in the case of presidential powers, the change was indeed spectacular. The appointments of Miroslav Poche and Michal Šmarda as ministers for the Social Democrats. The dismissal of Andrej Babiš from a ministerial post. Attempts to challenge ministerial nominees of Petr Fiala’s government after the 2021 elections. And finally, the conflict over Minister Petr Hladík, who was appointed only by Zeman’s successor. Incidentally, while Petr Fiala and Andrej Babiš either yielded to the president or gradually persuaded him, only Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka openly threatened Zeman with a competence lawsuit—an act worthy of recognition that unfortunately never became reality.

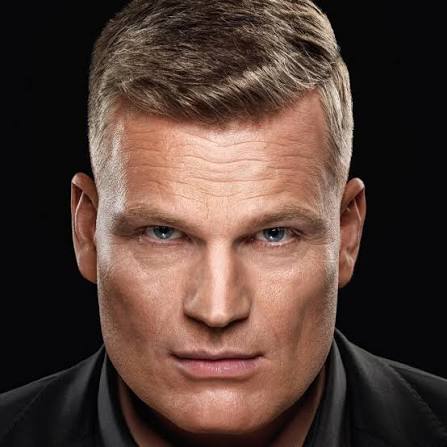

And today, it is happening again. The events surrounding Filip Turek and Petr Pavel have been discussed in the media for a long time, and now the situation has finally become clear. The president refused to appoint Turek as minister, supporting his decision with a long list of the candidate’s problems. The Motorists party and Turek himself loudly declared their willingness to continue the fight for a few days, but ultimately quickly agreed to a new compromise. The president allows their party leader to remain at the ministry, Turek receives the position of coordinator and de facto control over the ministry’s agenda, and Andrej Babiš can finally complete the formation of his government. A typically Czech solution. What is striking, however, is that the positions of those who once held very firm views against the actions of Miloš Zeman have now been completely reversed.

Hypocrisy and a Systemic Dilemma

For the sake of clarity: if anyone thinks this text is written in defense of Filip Turek’s personality or competence, let me state my opinion plainly. No—Filip Turek truly has no business holding any office, and this does not apply only to politics. If a person tries one day to curry favor with a pro-Western president and the next day shouts in Ukraine about problematic NATO expansion, then there is really no helping their intelligence. Personality, intelligence, or morality, however, are not factors that affect one’s right to actively participate in politics. From a legal standpoint, Filip Turek is (for now) fully capable of holding this office. And now the president has prevented him from doing so.

The above-mentioned reversal of opinions is particularly fascinating. “Mr. President, thank you for not appointing Turek.” This was written by MEP Danuše Nerudová on her X account on January 7. The same Danuše Nerudová who in 2021 evaluated Miloš Zeman’s attempts to interfere in the formation of Fiala’s government as follows: “The role of the president is not to influence the shape of the government, but to ensure a smooth transfer of power, especially at a time when we are in the middle of a pandemic crisis. Miloš Zeman received a mandate from voters to uphold the Constitution. Petr Fiala received one to form a government. Everything else wastes our time.” Certainly, we can discuss the need for swift approval during a pandemic, but the MEP speaks quite clearly here about the constitutional duties of the president—duties whose violation she now welcomes.

Another good example is a recent interview with the former Speaker of the Chamber of Deputies, Markéta Pekarová Adamová. “Unfortunately, only rather impolite expressions come to mind, but what they have done with the appointment of Filip Turek to some kind of coordinator position is an attempt— and I truly struggle to find polite words—to show the middle finger to the president and to all citizens. It is an attempt to wipe their backsides with the rules we have here and with how things are supposed to work.”

There are legitimate disputes about the legality of appointing Filip Turek as a coordinator, but pretending that this is an attack on the rules—by which she evidently means the presidential refusal—is absurd. Especially when in 2021 she wrote in this vein: “Miloš Zeman, July 1998: As for some kind of personnel veto, I believe it would be in conflict with Article 68 of the Constitution. Our list of ministerial candidates is complete and unchangeable.”

Both women, and many other politicians, commentators, and citizens who have suddenly completely changed their views on presidential powers, can of course counter with Miloš Zeman’s well-known remark about opinions and fools. But it is quite clear that the vast majority of them have simply decided to support their side of the ideological spectrum, regardless of the Constitution. In the case of both women, this is particularly disappointing to me, as I previously gave them and their parties my vote—but disappointment in politics is, unfortunately, a fact of life.

And Why Not Change?

The most interesting aspect of the whole matter is that citizens are largely unbothered by these presidential actions. In the case of Miloš Zeman, demonstrations were not organized over the refusal to appoint ministers, but over his other repugnant actions. Petr Pavel was briefly resented by ANO voters for not appointing Andrej Babiš, but the subsequent matter involving Filip Turek left them largely indifferent. Supporters of both men have repeatedly backed them on these issues, and their opponents have shown little interest. The president has long enjoyed stronger support than parliament, and direct election has made the office even more powerful. So why not take it to its conclusion? Is it not time for a full-fledged change to our political system?

I am not speaking here of the fantasies of Tomio Okamura and the former STAČILO coalition, who would interpret these words as the dismantling of democracy. Democracy must be defended at all costs. But that does not necessarily mean a parliamentary system. Many democracies operate under presidential or semi-presidential systems, and the willingness of Czech heads of state to bend the Constitution with impunity is already pushing us toward a semi-presidential system. Countries such as France have undergone this transformation, and the Czech Republic could choose a system that better suits its citizens.

I personally am a supporter of parliamentarism. Despite all its flaws, I cannot agree that a system modeled on the United States or France would be a better option for our country. Increasingly, however, it seems to me that our current system must either be strengthened again or completely redesigned. President Pavel may be very sympathetic to me, but he will not be in power forever. And anyone who thinks that someone like Miloš Zeman can no longer assume this office is absurdly naive. He can—and he could be far worse than the vindictive pensioner from Vysočina. President Pavel’s refusal to appoint Filip Turek sets yet another precedent that his successors may use for far greater and more dangerous actions.

Should the Constitution be replaced? For me, the answer is no—but it should be slightly updated. It would suffice to remove any role of the president in accepting ministerial nominations and leave him only a symbolic function in this process. This is how most parliamentary systems operate, and it would require changing only a single article of the Constitution. A transition to a presidential system would also have its advantages. The main problem with the actions of Miloš Zeman and Petr Pavel is not that they wield greater power, but the undermining of the Constitution that follows from their actions. The authority of the Constitution and our laws is the main pillar of the entire democratic system. We may disagree with them, and we have every right to change them legally. But their gradual collapse under a wave of hundreds of small blows is a certain path toward a future without even a trace of democracy.

Source: Médium